Football

Verne Lewellen: His Pro Football Hall of Fame credentials are beyond reproach

As a follow-up to last week’s citing of possible reasons for Verne Lewellen being snubbed by the Pro Football Hall of Fame, here’s more backdrop as to why he should have been inducted decades ago.

Just to be clear, this is in deference to NFL Films archivist and historian Chris Willis’ thoroughly researched profile of Lewellen in his recently published book, “The NFL’s 60-Minute Men: All-Time Greats of the Two-Way Player Era, 1920-1945.”

Willis ranked Lewellen the seventh-greatest player of the NFL’s first quarter-century of play, one spot behind Bronko Nagurski, and concluded: “His overall play at halfback puts him just below Dutch Clark, which is saying a lot. He deserves to be in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.” Clark was the No. 1-rated player in Willis’ book, and one of 12 running backs named to the NFL’s 100th anniversary all-time team.

- Lewellen played for the Packers from 1924-32. During those nine seasons, their record was 79-26-10, a .730 winning percentage based on the calculation covering ties that has been used by the NFL since 1972. Of the 10 quarterbacks on the NFL’s 100th anniversary team, only three – Cleveland’s Otto Graham (.810), Tom Brady (.754) and Roger Staubach (.746) – had a better winning percentage. Joe Montana’s percentage was .713; Peyton Manning’s .702.

Granted, during Lewellen’s first season-and-a-half, he sustained a dislocated shoulder that sidelined him for three games in 1924 and an ankle injury that kept him out of three more in 1925. Meanwhile, Curly Lambeau remained the Packers’ star player until he suffered a knee injury midway through the ’25 season that troubled him thereafter. In addition, Cub Buck, one of the best punters in the game at the time, did all of the Packers’ punting in ’24 and filled in when Lewellen was hurt in ’25.

Still, Lewellen had an impact as the small-town Packers finished 7-4 and 8-5, while losing by three points or less in five of their nine defeats.

“A new star is dazzling in the Packer football sky,” George Calhoun wrote in the Green Bay Press-Gazette when Lewellen returned from his injury as a rookie. “Lefty Lewellen arrived with bells on in the Milwaukee game.”

In Lewellen’s second season, following Lambeau’s injury and his own return to the lineup, there was no longer any doubt about him being the Packers’ budding new star.

In a 7-0 victory over Dayton, based on the Press-Gazette play-by-play, Lewellen caught back-to-back passes from a hobbling Lambeau for 58 yards and then scored from the 1-yard line on the final play for the game’s only touchdown, while also dictating field position throughout with his 14 punts, including a long of 58 and three that were downed inside the 20-yard line.

After the game, Ken Huffine, Dayton’s 6-foot-3, 208-pound fullback and a Collier’s Eye second-team all-pro the year before, told the Press-Gazette that Lewellen’s performance was one of the best exhibitions of football he had seen in years. “Speaking of educated toes, that boy Lewellen could punt a ball just where he wanted to. I never saw anything like it.”

Later that season, following a 13-7 loss to the Frankford Yellow Jackets, the Philadelphia Inquirer described Lewellen “as fleet and graceful a back as Frankford has seen this year, a man who ran back kicks for big gains and raced around the ends for still more yardage.”

That year, Lewellen was voted second-team all-pro based on a vote of 12 sports editors in other NFL cities taken by the Press-Gazette’s Calhoun. Second-team guard George Abramson was the only other Packer recognized.

Over the next four years, from 1926-29, Lewellen was named to the Press-Gazette’s first team based on polling of both sportswriters and team managers in each of the NFL cities. In 1930, Lewellen’s string of making all-pro was snapped, but he led the NFL with nine touchdowns and his punting was again the key factor in the Packers winning a second straight title.

There was no league MVP named at the time, but Willis retroactively chose Lewellen. As Willis wrote, “…he was one of the best at performing the two most important aspects of the two-way era: punting (field position) and scoring.” In 1930, the average number of points scored per game by the 13 teams was 10.3.

In 1931, Lewellen appeared on the verge of another all-pro season. Not only did he lead the league with five touchdowns after five games, he had been the difference-maker in back-to-back wins against the Packers’ most formidable foes, the Chicago Bears and New York Giants. In a 7-0 victory against the Bears on Sept. 27, Lewellen scored the only touchdown and ended the Bears’ last-ditch effort to tie the game by intercepting a pass at his 30-yard line on the final play. The next week, the Packers beat the Giants, 27-7, as Lewellen scored the game’s first two touchdowns and averaged 48.7 yards on three punts.

At age 30, an injury-riddled Lewellen had missed seven games that season. Still, he shined again in the next-to-last game by scoring the only touchdown and booming punts of 55, 55 and 59 yards to dictate field position as the Packers clinched their record third straight NFL championship with a 7-0 victory over Brooklyn.

“Lewellen, most publicized and most idolized of all Packer string in the cast, in four trips here has become practically synonymous with Packers in the minds of the fans,” A.D. Gannon of The Milwaukee Journal’s New York News Bureau wrote in his game story. “Appearing for the first time in Brooklyn, Lewellen, his punts and his touchdowns will live in the minds of fans across the bridge. He was an invaluable addition to the lineup on a wet field, booting high and mighty spirals…”

Lewellen played in all 14 games in 1932, his final season, and shared punting duties with youngsters Arnie Herber and Clarke Hinkle, but filled a backup role and scored only one touchdown.

In summary, when Lewellen was the Packers’ unquestioned star and at the top of his game, starting with the last six games of the 1925 season through the first five in 1931, the team’s record was 49-16-1, for a .750 winning percentage. It was a record over essentially six seasons that was even better than his career mark and only .004 percent behind Brady.

- As for big plays, nobody on the Packers came close to matching Lewellen in his time, and that may have been true of all his contemporaries throughout the entire league.

As Willis pointed out, Lewellen held the NFL record with 51 touchdowns when he retired, and that total stood until Don Hutson broke it in 1941, his seventh season. And to punctuate how important a single touchdown could be in Lewellen’s era, the Packers were 37-5-2, a remarkable .864 winning percentage, in games when he scored at least one touchdown.

Here are other big-play numbers provided by Eric Goska, the foremost authority on Packers statistics, for 96 of the team’s 102 games over Lewellen’s nine seasons.

He had the most runs of 10 yards or more with 49 followed by Lambeau with 27 and Johnny Blood with 26. As for pass receptions of 20 yards or more, Lewellen and Blood were tied for the most with 23. End Lavvie Dilweg had 20.

Esteemed football historian David Neft, an editor of The Football Encyclopedia, has exhaustively researched NFL statistics for the pre-stats era. Based on his unofficial and sometimes partial league-wide numbers, Lewellen finished his career as the NFL’s second-leading scorer, second-leading rusher, fifth-leading receiver in terms of receptions, tied for fifth in interceptions and 11th in passing, despite never being the Packers’ primary passer.

As for big games, Willis addressed Lewellen’s biggest: the Packers’ 20-6 victory over the Giants, which decided the 1929 NFL championship. Forced to play quarterback because of an injury to starter Red Dunn, Lewellen completely outplayed the greatest passer of the 1920s and future Pro Hall of Famer Benny Friedman. The Packers finished 12-0-1; the Giants, 13-1-1, when the league title was decided by the conference standings.

Thanks to a Lewellen punt on first down of the Packers’ first possession of that showdown, they gained a foothold they never lost.

Based on the Journal’s game story, as well as others in New York and Chicago newspapers, Lewellen boomed a 72-yard punt that was downed at the Giants’ 5-yard line. The Giants responded with a Tony Plansky first-down punt that traveled 32 yards, an exchange that flipped field position in the Packers’ favor by 38 yards within the first five plays of the game. Starting at the Giants’ 37-yard line, Lewellen then led a drive highlighted by his only two passes: a fourth-down, 12-yard completion for a first down and a fourth-down, 4-yard completion for a touchdown to give the Packers a lead they never relinquished.

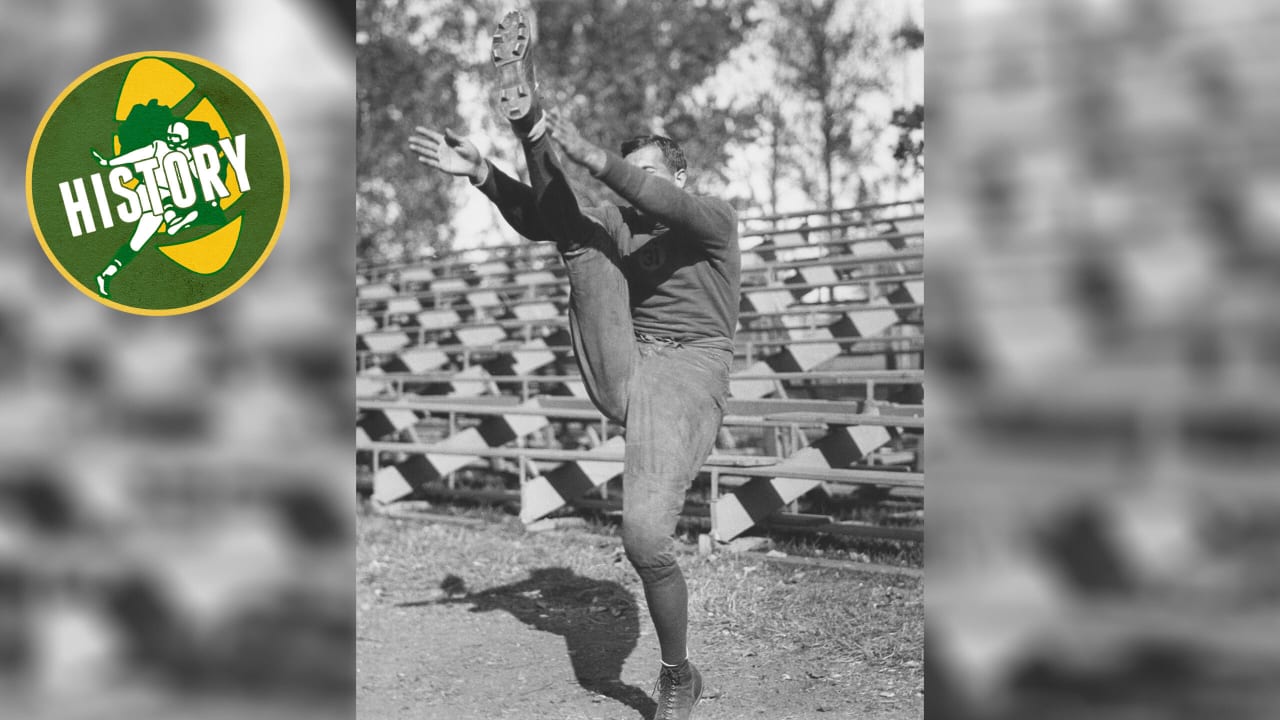

- None of the above statistics fully cover Lewellen’s greatest strength: his punting. At a time, when the position of punter, was arguably the most important in football, Lewellen was recognized as having no peers.

In Green Bay, for sure, there was no question about what was the Packers’ most vital position; and the reason they surpassed the Bears and Giants as the NFL’s most dominant team while compiling the best record in the league over the course of Lewellen’s career.

The Bears, from 1924-32, were 71-34-22, a .646 winning percentage, compared to the Packers’ .730. Actually, the Giants, who didn’t join the league until 1925, Lewellen’s second season, were ahead of the Bears with a .660 winning percentage, based on a 68-33-8 record.

When the Packers won their three consecutive titles from 1929-31, they were 11-3 against the Bears and Giants, including five shutouts and another game where they allowed only a safety in their seven victories over the Bears.

Neft credited Lewellen with a 39.4 average on a staggering 677 punts, more than twice Paddy Driscoll’s total. The Bears’ Driscoll was the league’s second-most prolific punter during that era with 260 attempts.

Before digging deeper into the numbers, the first point that needs to be made here is that Lewellen’s average per punt is profoundly misleading.

By all accounts, there was no punter who could come close to matching Lewellen for distance and hang time. But his specialty was the coffin-corner kick, at a time when a ball downed within five yards of the sideline was spotted there even if it was just a yard inside the field of play. As a result, that led to what was referred to at the time “as wasted downs,” offenses intentionally running the ball out of bounds on first down to have it spotted 10 yards from the sideline on second down.

A second point is that hereafter, I’m going to use numbers provided by Goska. His might differ slightly from Neft’s but what’s truly remarkable is how close they come to matching, considering how much research was involved in their work and done independently of each other. Goska has spent years and countless hours compiling the Press-Gazette’s play-by-plays from 1923, when they were first published regularly, through 1931, the last season before the NFL started keeping at least some official stats.

In 1928, Lewellen was credited with 136 punts. In the 84 years that the NFL has included punting among its official stats, no punter on a winning team has had more than 111 attempts.

But let’s focus on the three seasons when the Packers set a record for consecutive titles that has been matched only by Vince Lombardi’s 1965-67 three-peat champs. The numbers include 39 of Lewellen’s 42 games from 1929-31.

In all, he punted 196 times. Forty-five of those punts, almost one-fourth of them, traveled 50 yards or more, including 22 of 60 yards or more. Fifty-two of his punts were downed inside the 20-yard line and 23 resulted in returns of zero yards. As for overall returns, opponents produced only five of 20 yards or more and none longer than 35.

Here’s why Lewellen’s overall average is misleading. He punted 39 times, or one-fifth of the time, when the Packers were in possession of the ball in opponents’ territory. Eleven times he punted from the opponents’ 40-yard line or inside of it, including once from the 19.

What’s more, he punted only 65 times on fourth down. Two-thirds of his punts were basically intended to dictate field position – not the result of a defensive stop. Here was the breakdown of his other punts: first down, 44; second down, 21; third down, 65; and the down couldn’t be determined for another.

“Kicking then was their main offensive threat,” then Philadelphia Eagles president and coach Bert Bell wrote of the offensive mentality during the Knute Rockne era (1918-30) in Spalding’s 1939 National Football League Guide. Kicking, by the way, meant punting back then. In Lewellen’s nine seasons, the Packers kicked a total of 16 field goals, including only two in their three championship seasons.

In essence, Lewellen’s punting was the Packers’ featured weapon.

He punted 10 times or more on five occasions, and the Packers were 5-0 in those games, including three shutouts and another where Frankford scored only on a safety. Lewellen punted 15 times in that 14-2 victory against a Yellow Jackets team that would finish in third place with a 10-4-5 record in 1929. Two of the other victories were over the Bears: 25-0 in ’29 and 13-12 in 1930.

Something else that jumps out in the 96 play-by-plays available for Lewellen’s 102 games with the Packers is how often his name appears, when only the players who touched the ball on a given play were listed. According to Goska, the Packers ran 6,236 plays in those games, including punts, and Lewellen was involved in 27 percent of them.

Today, it’s common for quarterbacks to pass on more than 50 percent of their team’s offensive plays. Dunn, the Packers’ quarterback and featured passer on their three championship teams, threw a total of 159 passes from 1929-31, or 37 less than Lewellen’s punt total. Dilweg, the Packers’ great two-way end of the Iron Man era and the 36th-ranked player on Willis’ list, was involved in only 45 offensive plays from 1929-31.

Willis quoted some former players who continued to closely follow the NFL into the 1980s and claimed they never saw a better punter than Lewellen.

“His high, lazy punts regularly travel 60 yards through the air,” said Red Grange. “I once saw the ball travel between 75 and 80 yards from his foot to the point where it struck the ground. He places the ball to spots where it is almost impossible for the safety man to catch it, so that it usually rolls for many extra yards. He practices punting for hours at a time and can kick within 10 feet of a designated point.”

The New York Times’ Arthur Daley, who started covering pro football in the 1920s and was a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame’s original selection committee, covered Sammy Baugh, owner of a 45.1-yard punting average, and all the other great punters of the NFL’s first four decades. Here’s what he wrote in 1962: “No one who ever saw Lewellen kick could ever forget him. He was the finest punter these eyes ever saw.”

)