Tennis

Professional grass court tennis dies in North America

IT WAS the birthplace of lawn tennis in the US but now it has become its graveyard. The historic and venerable Newport Casino, which opened its doors to tennis, not gambling, in August 1881 for the first US National Lawn Tennis Championship, will close them this summer when it hosts its last major men’s tennis tournament. That moment will mark the end of professional grass court tennis in North America.

The Hall of Fame Open in its current professional form has been held since 1976 in Newport, Rhode Island, a patrician summer resort town where the cliff-top mansions are referred to as “cottages.”

Also housed on the grounds is the International Tennis Hall of Fame, its gables, latticework and fading cedar shingles lending an air of nostalgia that has been lost from the rest of the tennis tour with Wimbledon a possible exception.

“It’s the end of the chapter, not the end of the book,” says Newport tournament director Brewer Rowe, who hopes to bring other tennis events to the venue next year.

Newport is an ATP 250 category tournament, the lowest tier on the regular men’s tour, behind the four Grand Slams, the ATP Masters and the 1000 and 500 events.

“The 250s, even though it’s two-thirds of the tour, are looked at differently,” Rowe said. “They are not considered premium content.” A 250 grass court tournament in Mallorca, Spain, has also been struck from the ATP Tour calendar in 2025.

That’s a mistake, says Vijay Amritraj, the graceful Indian player who won the singles title at Newport three times and the doubles twice over a 10-year span between 1976 and ’86.

With grass his favourite surface, he also achieved quarter-final finishes at Wimbledon in 1973 and ’81. Amritraj will be inducted into the Tennis Hall of Fame this July, alongside fellow Indian player and doubles specialist Leander Paes and British journalist Richard Evans.

While he appreciated the nostalgic and tranquil atmosphere at Newport, the tournament’s departure and the loss of grass court events is less important, argues Amritraj, than developing a greater presence for the sport elsewhere in the world. The smaller events, especially, provide a crucial stepping stone for players making their way up the rankings, he says.

“The growth of tennis across the world needs to belong to the 250s,” Amritraj said. “That’s where everyone is going to get a chance to play and the world is going to see professional tennis. Not everyone needs [Carlos] Alcaraz and [Jannik] Sinner to play in their tournaments.”

Instead, there are huge geographical gaps on the ATP Tour, most notably in the global South. “During my time playing in the ’70s and ’80s, literally every capital in Asia had a tournament,” Amritraj says. “Now, if you leave China out of the mix, we have just the one in Tokyo. Africa doesn’t have one tournament. It’s a blank page.”

US grass court exponent Tim Mayotte, who reached the Wimbledon semi-finals in 1982 and was runner-up to Amritraj in Newport in 1984, agrees that the void in Third World tournaments and players from those regions needs addressing by the tour.

“The question is ‘how’?” Mayotte says. “The finances are impossible. Everybody needs a sponsor.” To get tournaments jump-started in Africa, a region with a youthful population that, says Mayotte, “could control the world economy in 75 years,” will take finding “an angel investor.”

Mayotte is working with a 23-year old Moroccan who, he says, “could have been a world-class player. But there’s just no backing. It’s so sad.”

Even in India, a country with large pockets of extreme wealth, and where Amritraj has devoted considerable efforts towards developing players, the results have been disappointing.

“The last male player [from India] to play on the Centre Court at Wimbledon is still me,” he said. “That’s a terrible thing to have to still say.”

There will be one Indian player in the men’s main draw at Wimbledon this year, “the first year in a couple of decades.” Four Indians will compete in the men’s doubles. The highest-ranked female player from India is Ankita Raina at 216.

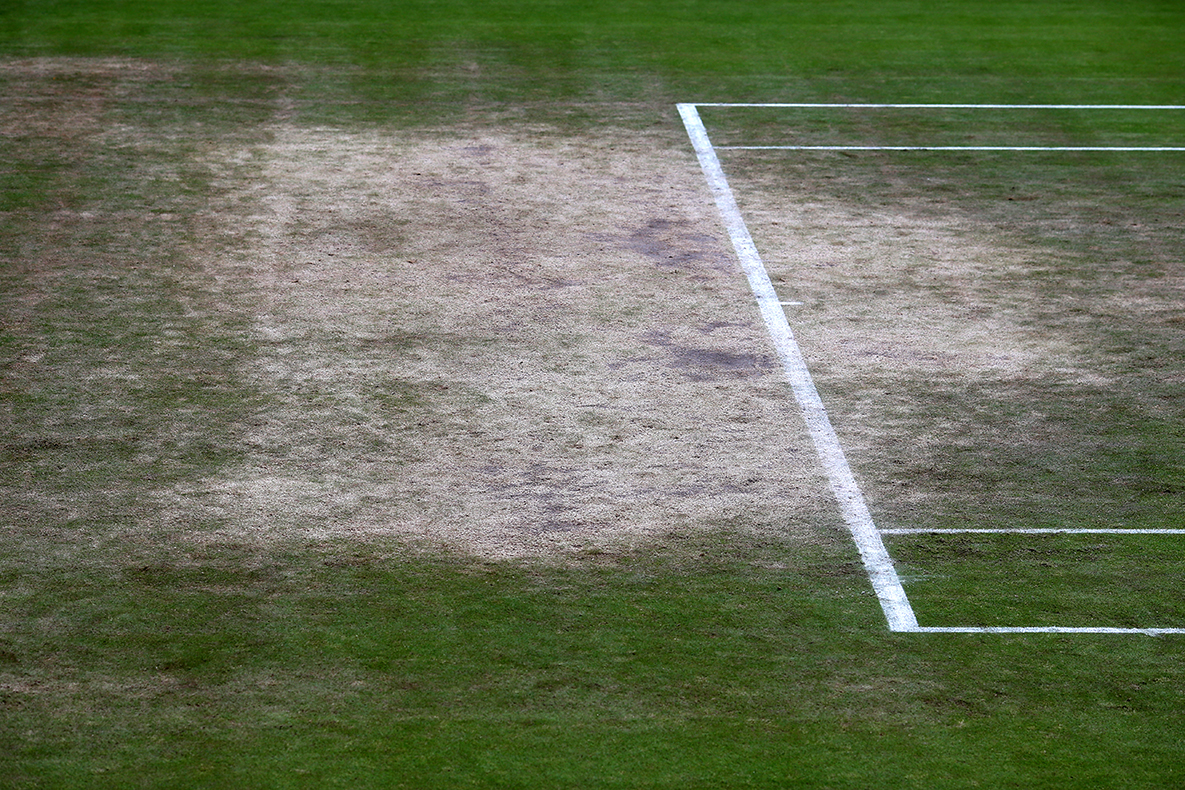

The death knell of grass court tennis in the US does not mean, however, that the hallowed grass at Wimbledon is in jeopardy. “I don’t think the championships are going anywhere at the All England Club and players will want to play on grass,” said Newport’s Rowe. And once in a while, Wimbledon even came to Newport.

“To have Sir Andrew Murray was awesome,” said Rowe, recalling Murray’s participation in the Hall of Fame Open in 2022 after the Brit had already won five Grand Slam titles, including two at Wimbledon. “It just elevated the event to a whole different level,” Rowe said. “He was a rock star for the tennis community here in Newport.”

Linda Pentz Gunter is a writer based in Takoma Park, Maryland.

)