Jobs

GenAI impact on jobs: doom or boon?

Podcast (english): Play in new window | Download (Duration: 13:05 — 6.0MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | Blubrry | Email |

What is the likely impact of AI and GenAI in particular on jobs, especially in Europe? Two recent reports on the topic, one in the UK and another one in France shed light on this question. According to the French report, such impact could amount to 5%. Yet another case for precision vs accuracy. That figure seems counter-intuitive when so many self-proclaimed AI gurus, especially on LinkedIn, are hailing the GenAI “revolution“. Besides, the authors of the UK report don’t agree at all with that. As ChatGPT would have it, let’s “delve” into those reports and find out more.

GenAI impact on jobs: boon or doom?

Our own empirical analysis suggests a positive effect of AI on employment in companies that adopt AI, because AI replaces tasks, not jobs. In 19 out of 20 jobs, there are tasks that AI cannot perform. Jobs that can be directly replaced by AI would therefore represent only 5% of jobs in a country like France. What’s more, the generalisation of AI will spur job creations, in new occupations as in old ones. To sum it all up, some industries or geographies could experience net job losses, therefore requiring Government support, but this does not mean that AI will have an overarching negative effect on national employment in France.

French Commission on Artificial Intelligence report, March 2024 – p. 41

Anxiety in the eyes of some of my younger students

I often talk to young students from all areas about the impact of GenAI on jobs and careers. I often sense a bit of reticence and even anxiety in them at a time when young adults are still asking themselves many questions about the future and aren’t necessarily clearly determined about what they want to do in the future. Beyond that, the current state of hype around GenAI further blurs these students’ vision by making them feel the weight of an uncertainty that is already difficult for some to stomach.

- Recent reports have added fuel to the fire, such as this one from the IMF.

Almost 40 percent of global employment is exposed to AI, with advanced economies at greater risk but also better poised to exploit AI benefits than emerging marketMarket definition in B2B and B2C – The very notion of “market” is at the heart of any marketing approach. A market can be defined… and developing economies. In advanced economies, about 60 percent of jobs are exposed to AI, due to prevalence of cognitive-task-oriented jobs. A new measure of potential AI complementarity suggests that, of these, about half may be negatively affected by AI, while the rest could benefit from enhanced productivity through AI integration.

IMF 2024 report on AI and the impact on employment and the future of work

The British government has also published a report on this subject. Its more task-oriented approach is a little more nuanced, but still fairly unappealing.

Advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI) are likely to have a profound and widespread effect on the UK economy and society, though the precise nature and speed of this effect is uncertain. It has been estimated that 10-30% of jobs are automatable with AI having the potential to increase productivity and create new high-value jobs in the UK.

Gov.uk report on the impact of AI on jobs, Nov 2023

It’s worthy of note, however, that the authors are resorting a great deal to the conditional tense. This undoubtedly urges us to interpret these results with caution.

A more nuanced report on the impact of AI on jobs

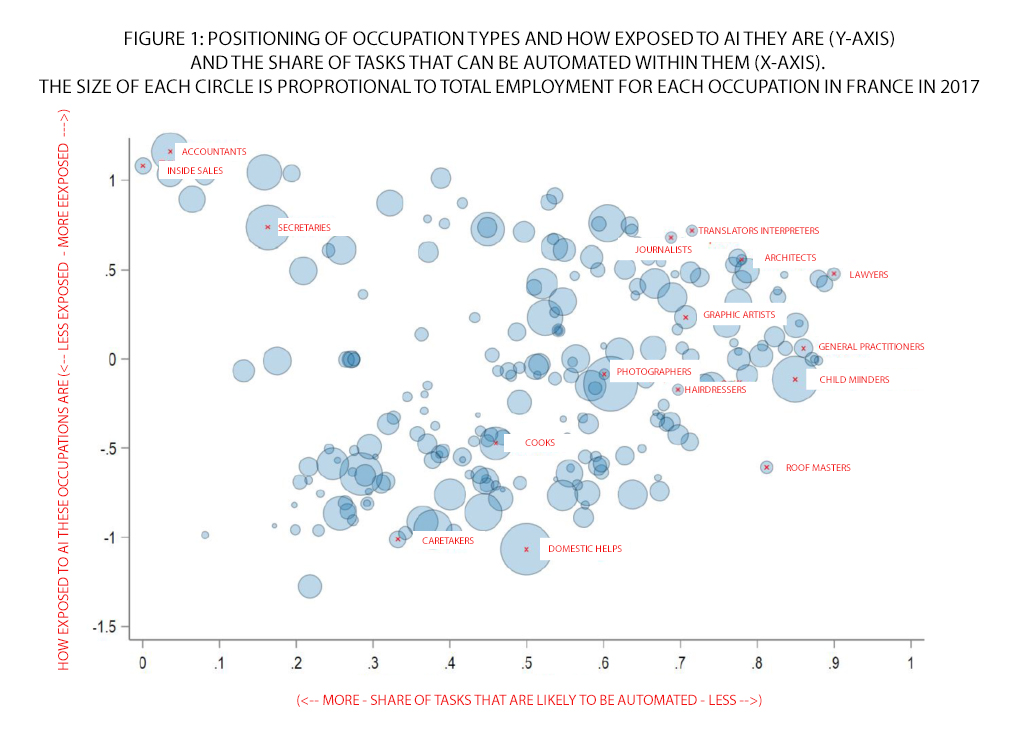

The French report is much more nuanced and refers to a large number of interesting studies, starting with the one by Antonin Bergeaud (an economist and professor at the Paris H. E. C. School of Management), from which I extracted an important schematic.

The approach of the French report makes a clear distinction between GenAI and AI, and even automationMarketing automation in B2B enables marketing processes to be managed automatically across multiple channels. With marketing automation, companies can target their visitors with automated messages via e-mail, the web, social networks and SMS. Marketing Automation in B2B Above is a diagram explaining how the scenarios work in marketing automation, based on behavioural scoring and profiles. Messages are sent automatically, according to sets of instructions called workflows. The Limits of B2B Marketing Automation Some companies install marketing automation mechanisms while their maturity on the subject is ‘under construction’. They deploy technology for technology’s sake which leads them to use tools that in the broad sense (i.e. aimed at the manufacturing industry). It’s a distinction that seems crucial to me, given the many misconceptions linked to the measuring of the impact of AI. Which AI? Generative AI? Machine Learning, deep learning, neural networks? Or even just plain good old IT, unless we are mentioning robotisation, automated supply chains…

In short, AI is everything and everything is AI. That seems to me a silver bullet for generating panic among the general public and especially young students who are trying to find their way in the future.

A More Thorough and Subtle Report

The French report is therefore more precise than the others I’ve read, in that it makes a clear distinction between GenAI and the others. It is also focusing on tasks rather than jobs. This approach has also been that of the British government.

- The report is in disagreement with previous approaches, pitting them against each other and pointing out that, in the end, there may be no need to panic:

This approach using the exposure of tasks, vs jobs, to GenAI makes it possible to estimate aggregate effects at the level of the economy as a whole, and to allow comparisons between countries. However, it has several limitations. Here are the two main ones. On the one hand, it is a static approach: the studies are based on existing tasks and therefore do not take account those tasks that could be created as a result of the development of AI […] On the other hand, it is based on an estimate of the probability of different tasks being replaced by AI (see above diagram).

In short, even if you think it’s a better approach, thinking of the impact of AI in terms of tasks isn’t really possible. It’s like painting a picture of a landscape from the window of your intercity train at 100 miles per hour. On top of that the painter has left his glasses at home and is therefore making assumptions about whether he should add cows, or sheep, in the meadow in his painting.

[…] overall, the deployment of AI in the economy should have a positive effect on the number of jobs. Catastrophic predictions about the end of work are no more credible than similar predictions made in the past. Especially as even the task-based approach represents the upper limit for the impact of AI. Indeed, it makes the assumption that it is profitable to automate all the tasks that can be automated. But this assumption is far from being true today. The diminishing cost of AI systems and the possibility of distributing the same AI system to a very large number of users will be key factors in determining the impact of GenAI on tasks and jobs.

Antonin Bergeaud

In conclusion, if the result is not negative, it must be positive, even if it is undoubtedly just as difficult to prove as the opposite.

Five percent impact of GenAI on jobs… why not 5.2%?

As for the 5% figure announced in the French report (see the quote above), I suppose it should be taken as an order of magnitude. There is a nuance added to the report in that respect. The authors mention that these 5% may vary from one occupation to another. What I take from this is that for the vast majority of occupations, this figure of 5%, is probably not to be taken at face value. Some occupations will not be affected by artificial intelligence at all, especially generative artificial intelligence. This doesn’t come as a shock to us. It takes us back to our work on jobs in 2030, where we already showed the prevalence of non-automatable occupations (surface technicians and others) in the most sought-after professions.

Automation Is neither Easy Nor Happens Overnight

Occupations that are apparently easy to automate, such as bookkeeping, for example (if we fail to take its more consultancy-like aspects into account) have been on the chopping block for years. But despite the doomsday predictions, including our own, it has to be said today that the jobs of chartered accountants remain among the most in demand.

Yet all the technology is available to automate both bean counters’ tasks and data transmission. Nowadays, almost all invoices are dematerialised even though they are only unstructured PDF files. And yet most of the work of accountants remains manual whether we like it or not. Whether it’s ticking boxes between reconciliation systems or copying figures into a general ledger. The change lies mainly in the declining technical nature of the job.

Ditto for banking. Experts have been naming banks dinosaurs for years. Here again, we have to make amends. And yet there have been many restructurings, and they didn’t wait for OpenAI’s ChatGPT and its clones. But here’s the thing: changes don’t happen overnight. Besides innovation in organisations isn’t governed by wizardry but resistance to change.

Finally, let’s return to an occupation that was in the top left-hand corner of Antonin Bergeaud’s schematic. I mean that of secretaries. An occupation that has already been largely transformed since the 1990s. It has also been steadily declining to the point of disappearance at least in the United States (they only amount to a fraction of European employees now, i.e. a small proportion of 19% of all jobs). And yet, the impact of artificial intelligence between the 1980s and the year 2000 was bound to be close to zero. I should know, I was in charge of an AI project in those days. In that same period, though, I witnessed and even played an active role in the boom of the deployment of IT in businesses.

GenAI and jobs: looking at the big picture

We therefore need to get back to these forecasts with a critical look. Starting with those of the IMF. And this report by the French Committee on Artificial Intelligence deserves credit for playing down the most hairy-fairy statistics on this subject.

In conclusion, after reading all these reports, the future isn’t any more predictable than it was before that. We might even venture to say that we are even more confused. Admittedly, as the authors of the French report point out, we are already seeing, and will continue to see, employees that are made redundant in professions where business models are already being jeopardised by ICTs, such as journalism.

But is this sufficient for us to reckon that what we are going through today is a “revolution” in terms of employment? There are no indications on this. All we could surmise is that a minority of jobs will be hit — be it 5%, less or more.

Time will tell whether this figure or that of the International Monetary Fund was the right one, but I’m inclined to believe that the ballpark figure quoted by the French Artificial Intelligence Commission is closer to reality.

Predictions lie but figures don’t

Finally, to end on an intellectual note, let’s quote Vaclav Smil in his book Numbers don’t lie.

Being realistic about innovation

Modern societies are obsessed with innovation.

We are to believe that innovation will open every conceivable door: to life expectancies far beyond 100 years, to the merging of human and machine consciousness, to essentially free solar energy.

This uncritical genuflection before the altar of innovation is wrong on two counts: It ignores those big, fundamental quests that have failed after spending huge sums on research.

And it has little to say about why we so often stick to an inferior practice even when we know there’s a superior course of action.

Vaclav Smil, Numbers don’t lie

It’s this last sentence that I think is important. All forecasting exercises start from an assumption: that which state that when a technology improves our lives, it’s bound to be implemented.

It may seem like a no-brainer at first glance. What I have learned in the field throughout my career, however, is that when a solution is better, especially when it is better, resistance to change is all the greater. And it’s rarely the most obvious and cost-effective solutions that win. Especially because human decisions are seldom rational.

Thus, assuming that generative AI is without contest a boon to productivity gains, a theory I’m not at all sure I buy into, it would be wrong to believe that the mere fact that it exists guarantees its rapid and universal implementation.

Here again, time will be of the essence.

)