Infra

Cuba Ransomware Deploys New Tools: BlackBerry Discovers Targets Including Critical Infrastructure Sector in the U.S. and IT Integrator in Latin America

Note: The following is a redacted version of a larger report. For full and comprehensive details of this attack, please enquire about our CTI-on-demand service.

Summary

BlackBerry has discovered and documented new tools used by the Cuba ransomware threat group.

Cuba ransomware is currently into the fourth year of its operation and shows no sign of slowing down. In the first half of 2023 alone, the operators behind Cuba ransomware were the perpetrators of several high-profile attacks across disparate industries.

The BlackBerry Threat Research and Intelligence team investigated a campaign by this threat group conducted in June that culminated in attacks on an organization within the critical infrastructure sector in the United States, and also on an IT integrator in Latin America. The Cuba threat group, believed to be of Russian origin, deployed a set of malicious tools that overlapped with previous campaigns associated with this attacker, as well as introducing new ones — including the first observed use of an exploit for the Veeam vulnerability CVE-2023-27532.

Note that prior to the publication of this report, BlackBerry shared this information privately with the relevant authorities, to support security and resilience across organizations worldwide.

This report documents our findings and breaks down the technical details of these latest attacks, and discusses in depth the latest evolution in tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) utilized by the Cuba threat group.

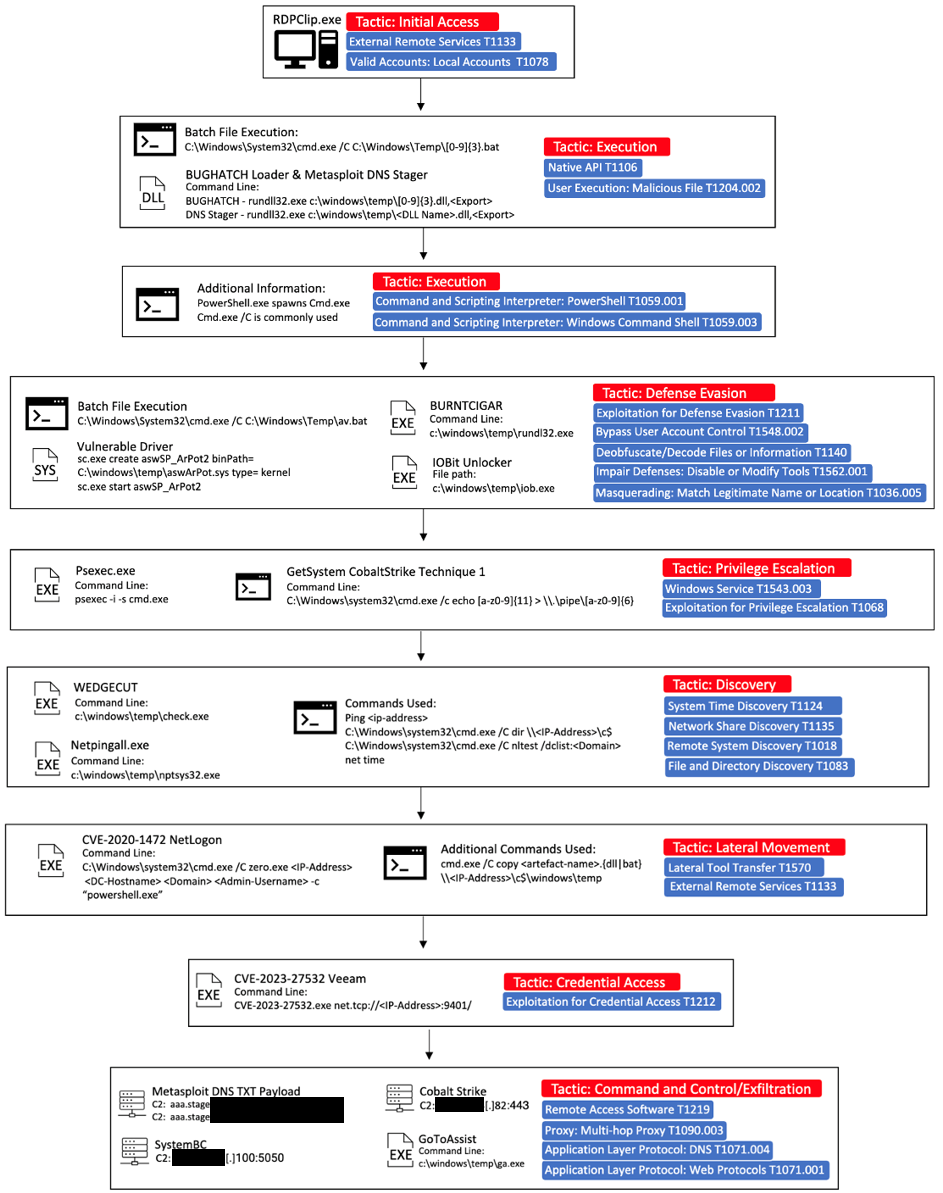

Brief MITRE ATT&CK® Information

|

Tactic

|

Technique

|

|

|

T1133, T1078.003

|

|

|

T1106, T1204.002, T1059.001, T1059.003, T1569.002, T1218.011

|

|

|

T1211, T1548.002, T1140, T1562.001, T1036.005

|

|

|

T1543.003, T1068

|

|

|

T1124, T1135, T1018, T1083, T1057, T1016.001

|

|

|

T1570, T1333

|

|

|

T1212

|

|

|

T1219, T1090.003, T1071.004, T1071.001, T1105

|

Weaponization and Technical Overview

|

Weapons

|

EXEs, DLLs, LOLBins, PS, Metasploit, Cobalt Strike, Exploits

|

|

Attack Vector

|

Credential theft, RDP

|

|

Network Infrastructure

|

TOR, IPs, Ports – 5050,443

|

|

Targets

|

U.S.-based critical infrastructure company; Latin America-based IT integrator

|

Technical Analysis

Context

In early June, as part of our ongoing monitoring of the Cuba threat group, we found evidence of an attack on a U.S.-based organization and decided to investigate. We uncovered a complete set of TTPs, many overlapping with previously seen Cuba attacks, and which encompassed a comprehensive attack toolset.

These included BUGHATCH, a custom downloader, BURNTCIGAR, an antimalware killer, Metasploit, and Cobalt Strike frameworks, along with numerous Living-off-the-Land Binaries (LOLBINS). We also found several exploits that have freely available Proof-of-Concept (PoC) code.

Who Are the Cuba Ransomware Group?

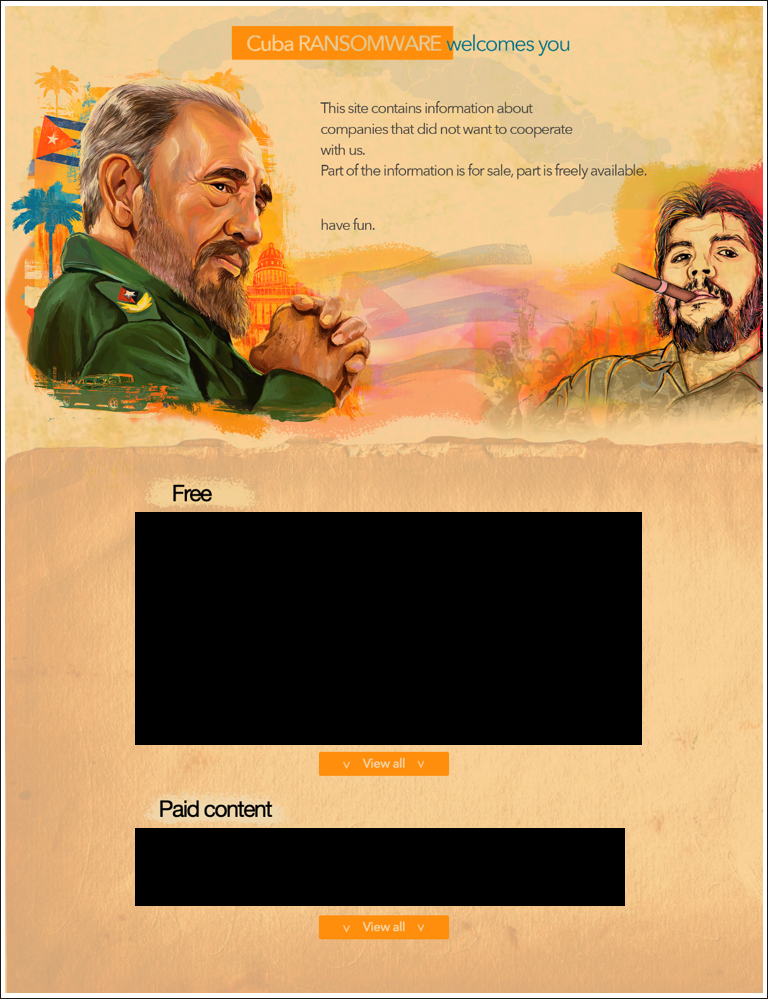

Figure 1: Cuba ransomware leak site

Cuba ransomware, also known as COLDDRAW ransomware, first appeared on the threat landscape in 2019 and has built up a relatively small but carefully selected list of victims in the years since. It is also known as Fidel ransomware, due to a characteristic marker placed at the beginning of all encrypted files. This file marker is used as an indicator to both the ransomware and its decoder that the file has been encrypted.

Despite its name and the Cuban nationalistic styling on its leak site, it unlikely has any connection or affiliation with the Republic of Cuba. It has previously been linked to a Russian-speaking threat actor by researchers at Profero due to some linguistic mistranslation details they uncovered, as well as the discovery of a 404 webpage containing Russian text on the threat actor’s own leak site.

Based on the strings analysis of the code used in this campaign, we also found indications that the developer behind Cuba ransomware is Russian-speaking. That theory is further strengthened by the fact the ransomware automatically terminates its own execution on hosts that are set to the Russian language, or on those that have the Russian keyboard layout present.

Like many ransomware operators, Cuba utilizes the double-extortion approach to “encourage” victims to pay up. Last fall, a joint advisory issued by U.S. law enforcement stated that as of August 2022, the Cuba ransomware group is believed to have compromised 101 entities, including 65 in the United States and 36 outside the United States. In that time it has demanded USD $145 million in ransom payments, and received up to USD $60 million.

Throughout the last four years, Cuba has used a similar set of core TTPs with a slight shift from year to year. These typically consist of LOLBins (executables that are a part of the operating system and can be exploited to support an attack), exploits, commodity and custom malware, and popular legitimate pen-testing frameworks such as Cobalt Strike and Metasploit.

Additionally, at one point in 2022, the group appeared to have developed a relationship with the operators of the Industrial Spy marketplace, using their platform as a leak site, based on similarities in both operators’ ransomware.

Also worthy of note is that Cuba’s own leak site has gone on and offline intermittently during the last couple months. Based on our observations, the site comes back online whenever a new victim is allegedly compromised and listed, before going dark again.

Attack Vector

Our analysis of the attack we analyzed led us to a credentials reuse scheme. The first evidence of a compromise in the targeted organization was a successful Administrator-level login via Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP). This login was achieved without evidence of prior invalid login attempts, nor evidence of techniques such as brute-forcing or exploitation of vulnerabilities. This means that the attacker likely obtained the valid credentials via some other nefarious means preceding the attack.

Previous Cuba attacks have exploited vulnerabilities or Initial Access Brokers (IABs) to procure access.

Weaponization

Cuba’s toolkit consists of various custom and off-the-shelf parts, many of which have been used during campaigns in the past and align with this group’s previously seen TTPs.

BUGHATCH

The first stage begins with the deployment and execution of BUGHATCH, a lightweight custom downloader likely developed by the Cuba ransomware members, as it has only been seen operated by them in the wild. It establishes a connection to a command-and-control (C2) server and downloads a payload of the attacker’s choosing, typically small PE files or PowerShell scripts. BUGHATCH also can execute files or commands, including giving the operator a choice on how a payload should be executed.

In previous campaigns, BUGHATCH was typically retrieved and deployed via a PowerShell dropper or loaded into memory by a PowerShell-based script. The campaign we investigated relies on four separate DLLs to fetch and load the “agent32/64.bin” BUGHATCH payloads.

All four DLLs use the Microsoft Foundation Class (MFC) Library and launch from various locations on compromised hosts; each had slight deviations in execution. This was performed by invocating specific exports through the “rundll32.exe” utility and specific commands.

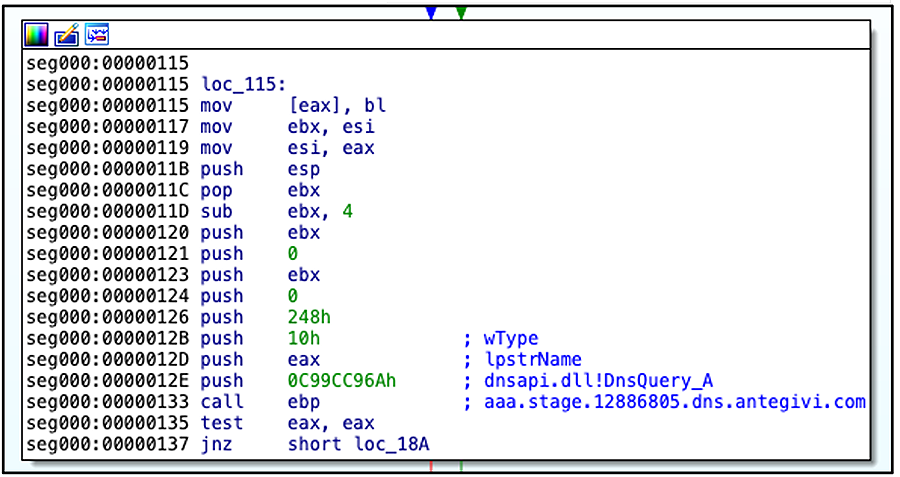

Metasploit DNS Stager

Metasploit was utilized by Cuba operators to gain an initial foothold within the target environment, specifically, their dns_txt_query_exec payload embedded within the DLLs. Once executed via specific exports, they will proceed to decrypt the shellcode in memory and run it.

The shellcode performs a TXT query upon a DNS record(s) set and then executes a returned payload.

Figure 2: DNS stager query C2

Wedgecut

That is a host enumeration tool that accepts an argument consisting of a list of IP addresses or hosts, then uses Internet control message protocol (ICMP) packets to check whether they are online. The binary observed in this campaign was an exact match (filename + SHA256) as the one documented previously by researchers in another Cuba breach in early 2022.

Defense Evasion

Numerous defense evasion techniques were performed as part of their order of attack. From attempting to uninstall endpoint protection manually, to group policy modification and (most notably), using the Bring Your Own Vulnerable Driver (BYOVD) technique.

BYOVD has garnered quite a lot of attention recently, but this technique is familiar to this group. Previous reporting by different vendors showed several variations of a tool dubbed by Mandiant as BURNTCIGAR being used before the deployment of Cuba ransomware to terminate endpoint security products.

BURNTCIGAR

BURNTCIGAR is a utility that terminates a given process on a kernel level. This known malware employs the DeviceIoControl function to exploit the undocumented I/O control node (IOCTL) codes of a vulnerable driver with whom it intends to interact. Several different drivers have been used in conjunction with this malware, such as aswArPot.sys, ApcHelper.sys, and KApcHelper_x64.sys, to name a few.

Observed in this campaign was the continued use of aswArPot.sys, KApcHelper_x64.sys, and in addition, the use of the vulnerable Process Explorer driver, procexp152.sys. This driver had been previously abused by Meduza Locker and LockBit earlier this year. These samples were loaded via simple batch scripts or, in the case of KApcHelper_x64.sys, a self-loading capability was embedded within.

Another difference was an under-the-hood update to the malware itself. In previous versions, it contained a cleartext hardcoded list of targeted processes to kill; however, in a variant seen in this campaign, the list was hashed with the CRC-64/ECMA-182 algorithm. Once decoded, it includes a list of processes overlapping with previous Cuba campaigns. We also observed several samples leveraging the Microsoft Foundation Class (MFC) Library, similar to what was seen with the BUGHATCH samples described earlier.

There was another deviation in execution. For the BURNTCIGAR samples that utilized the KApcHelper_x64.sys driver, a file called proname.dbt was used that contained the “kill” list of processes. That was then used to read from during process enumeration on the host to compare and terminate processes, should a match occur.

The final total kill list was seen to contain over 200+ targeted processes in total — many of which are anti-malware endpoint solutions and tools.

Exploits

We found two exploits deployed in this campaign, which align with previously seen TTPs from this group. The difference is that, as we know, this is the first time the Cuba threat actor used the vulnerable process CVE-2023-27532.

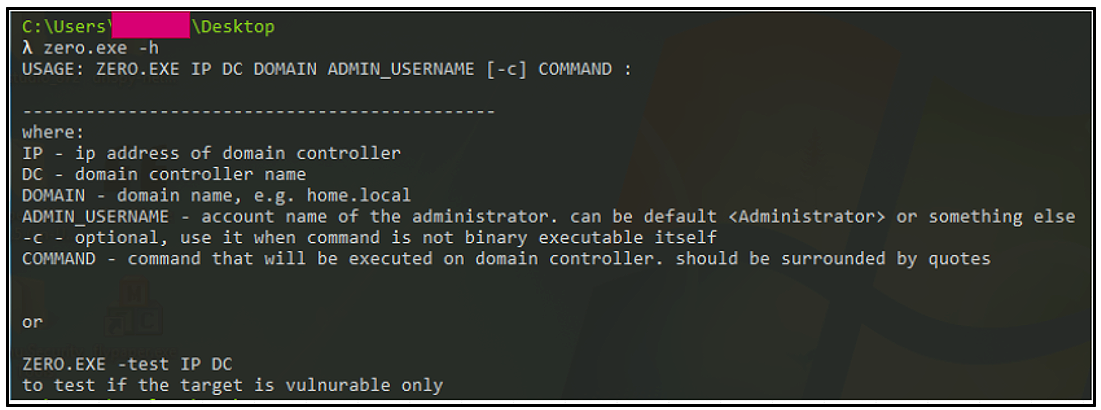

CVE-2020-1472 — NetLogon

This vulnerability involves Microsoft’s NetLogon protocol (MS-NRPC). It allows for an escalation of privileges against active directory (AD) domain controllers (DC) should an attacker use MS-NRPC to create a vulnerable connection to obtain admin access.

Dubbed “ZeroLogon” due to the initialization vector (IV) in the logon process being set all to zeros instead of random numbers, if successfully exploited, a threat actor could potentially compromise and take control of a vulnerable domain.

The binary used to exploit this vulnerability in this campaign is the same one previously used by the Cuba Operators across multiple attacks from 2022 to present.

Figure 3: CVE-2020-1472 exploit help option menu

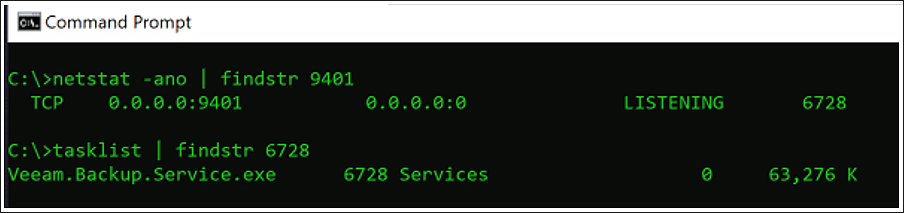

CVE-2023-27532 — Veeam

This vulnerability affects the legitimate Veeam Backup & Replication software, allowing an attacker to potentially gain access to the credentials stored within the configuration file on the victim’s device.

It is exploitable via the Veeam backup service, which runs on the default TCP port of 9401.

Several threat actors exploited this CVE when it was discovered, such as the Fin7 group in late March 2023.

The exploit works by accessing an exposed API on a component of the Veeam application — Veeam.Backup.Service.exe. This vulnerability exists on any version of the Veeam Backup & Replication software prior to the version 11a (build 11.0.1.1261 P20230227) and version 12 (build 12.0.0.1420 P20230223).

Figure 4: Vulnerable application on default port 9401

Other Notable Tools

The Cuba threat actor relied on several commonplace and built-in tools, such as ping.exe for discovery and cmd.exe for various purposes, such as lateral movement.

- cmd.exe /C copy

.{dll|bat} \\ \c$\windows\temp

Along with domain controller (DC) enumeration when leveraged in conjunction with the nltest utility, it is used with its /dclist switch to return a list of domain controllers when supplying the domain name of the target company.

- cmd.exe /C nltest /dclist:

The network management utility – net.exe – is used primarily to display the time synchronization on various hosts, and PSexec elevates privileges and pivots deeper within the network.

In addition to the LOLBins mentioned above, there is a netpingall.exe which, as its name suggests, is an enumeration tool that uses the Internet control message protocol (ICMP) to discover additional live hosts within a network. Interestingly enough, this is the same binary that was seen used in a Hancitor campaign just over two years ago.

The Cobalt Strike Beacon is also part of the toolset and is deployed post-exploitation for privilege escalation and C2 communications.

Figure 5: Main execution chain diagram

Network Infrastructure

The C2 infrastructure related to the delivery of the BUGHATCH malware observed in this campaign has been previously seen as indicators of compromise (IoCs) in past Cuba campaigns.

All three of the IPs were signed with an SSL certificate that upon pivoting on, was seen to be used to sign additional infrastructure.

The Cuba operators maintain a “.onion” webpage located on the dark web, which is accessible via the TOR network. The site is heavily themed with Cuban nationalistic styling, with pictures of the flag along with former leader of Cuba, Fidel Castro, and Che Guevara, who was a major figure of the Cuban Revolution. Guevara’s stylized visage has become a countercultural symbol of rebellion and global insignia in popular culture.

|

Domain name

|

Last Seen

|

|

hxxp://cuba—————–REDACTED——————–[.]onion.

|

08/09/2023 |

Table 1: Cuba Leak Site URL

The leak site also contains a list of alleged victims, along with their company logo and website address, basic info on the company, the date the files were ‘received’, and their leaks. Included is a high-level description of what stolen data is available. Also noted is whether the data is free or if it is available only in exchange for payment, depending on the sensitivity/ potential value of the data and the profile of the victim organization.

Figure 6: Cuba threat group’s leak site

An interesting point to note is that this site has appeared on and offline sporadically over the last several months, with it appearing to be brought back online for a short period to coincide with a new victim being allegedly compromised and listed, before going dark again.

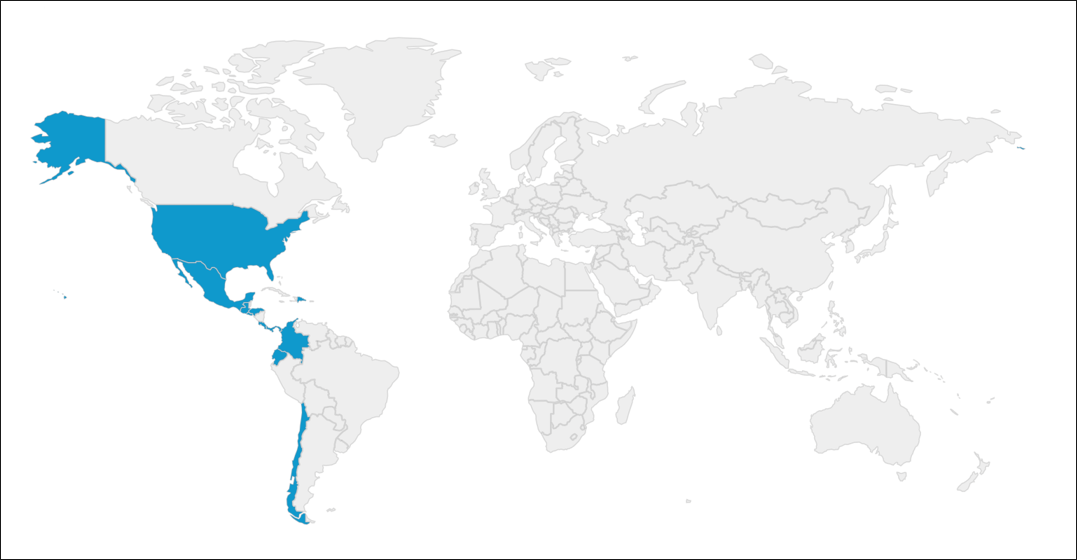

Targets

The targets for this campaign were a critical infrastructure company in the United States, and a systems integrator from Latin America.

Figure 7: Geolocation of victims targeted in this campaign

Attribution

Due to the very nature of campaigns that utilize ransomware, it is simple to conclude that the threat actor behind Cuba ransomware is financially motivated. Based on the aforementioned linguistic and text-based details documented by researchers at Profero, including the termination of execution on machines that have Russian language or keyboard layout present, it’s highly likely the threat actor/s behind it are Russian-speaking. Another significant clue to the Cuba group’s origins is the fact that throughout the whole course of the ransomware’s existence, its operator’s choice of victims has been predominantly Western-based (or allied), democratic, anglophone countries.

Conclusions

Our investigation indicates that the Cuba threat group continues to target entities in crucial sectors such as critical infrastructure.

The Cuba ransomware operators continue to recycle network infrastructure and use a core set of TTPs that they have been subtly modifying from campaign to campaign, often adopting readily available components to upgrade their toolset whenever the opportunity arises. An example of this is a change in the use of exploits for key vulnerabilities; whereas they have been previously seen exploiting CVE-2020-1472/ Zerologon, this appears to be the first time they targeted CVE-2023-27532/ Veeam.

In addition, the threat actor has made some under-the-hood modifications to some of their custom tooling, likely as a mechanism to impede both detection and analysis, as was seen with the inclusion of the hashing functionality to BURNTCIGAR’s codebase.

Any updates are likely designed to optimize its execution during campaigns, and we expect to see persistent activity from this group in the near future.

Cuba Ransomware: Mitigation Recommendations

- Ensure that an up-to-date patch management program is in place.

- Implement an adequate email gateway solution to help prevent phishing and block spam emails, which are used as an initial infection vector.

- Proper segmentation of networks can help slow or contain an attack by Cuba ransomware, should a breach occur.

- Implement a robust and up-to-date comprehensive data backup solution.

- Deploy an AI-equipped endpoint protection platform that protects against Cuba ransomware, such as CylanceENDPOINT™.

- Implement security awareness training and conduct lessons on a regular basis, focused on establishing good cyber-hygiene practices.

- Ensure a modern firewall solution is in place.

- Enforce VPN and Multi-Factor Authentication (2FA) solutions for connection to internal networks.

APPENDIX 1 – Referential Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

|

Hashes (sha-256)

|

|

|

58ba30052d249805caae0107a0e2a5a3cb85f3000ba5479fafb7767e2a5a78f3

|

Agent32.bin BUGHATCH

|

|

3a8b7c1fe9bd9451c0a51e4122605efc98e7e4e13ed117139a13e4749e211ed0

|

CVE-2020-1472 Netlogon Exploit

|

|

cf87a44c575d391df668123b05c207eef04b91e54300d1cbbec2f48f5209d4a4

|

CVE-2023-27532 Veeam Exploit

|

|

765d84ae85561bf5dbc1187da2b2cef91da9f222bcc6cf2c12cacd36e44bcffd

|

Metasploit DNS Stager

|

|

1c2d7f19f8c12e055e1ba8cdf5334e6cb5510847783fbe36121a35ad70f09eb3

|

BURNTCIGAR

|

|

9b1b15a3aacb0e786a608726c3abfc94968915cedcbd239ddf903c4a54bfcf0c

|

KApcHelper_x64.sys

|

|

4b5229b3250c8c08b98cb710d6c056144271de099a57ae09f5d2097fc41bd4f1

|

aswarpot.sys

|

|

075de997497262a9d105afeadaaefc6348b25ce0e0126505c24aa9396c251e85

|

procexp152.sys

|

|

bd93d88cb70f1e33ff83de4d084bb2b247d0b2a9cec61ae45745f2da85ca82d2

|

netpingall.exe

|

Network Indicators

|

Available upon request – see below.

|

APPENDIX 2 – Applied Countermeasures

Yara Rules

|

Available upon request – see below.

|

Suricata Rules

|

Available upon request – see below.

|

APPENDIX 3 – Detailed MITRE ATT&CK® Mapping

|

Available upon request – see below.

|

Disclaimer: The private version of this report is available upon request. It includes, but is not limited to, the complete and contextual MITRE ATT&CK® mapping, MITRE D3FEND™ countermeasures, Attack Flow by MITRE, and other threat detection content for tooling, network traffic, complete IoCs list, and system behavior. Please email us at cti@blackberry.com for more information.

For similar articles and news delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe to the BlackBerry Blog.

)