“We felt like this project could really make a difference”

If you’re sitting while you read this, you’ll likely shift your weight before you reach the last sentence. You won’t think about it – around two-and-a-half minutes in (research shows), you’ll notice pressure building on some part of your back or behind. You probably won’t even pause between words as you move to relieve the discomfort.

It’s not that easy for a wheelchair user who may not have enough strength in their arms to help. The results of being unable to make that simple fix can be dire, leading to pressure sores, which can become infected, which can lead to fatal blood poisoning.

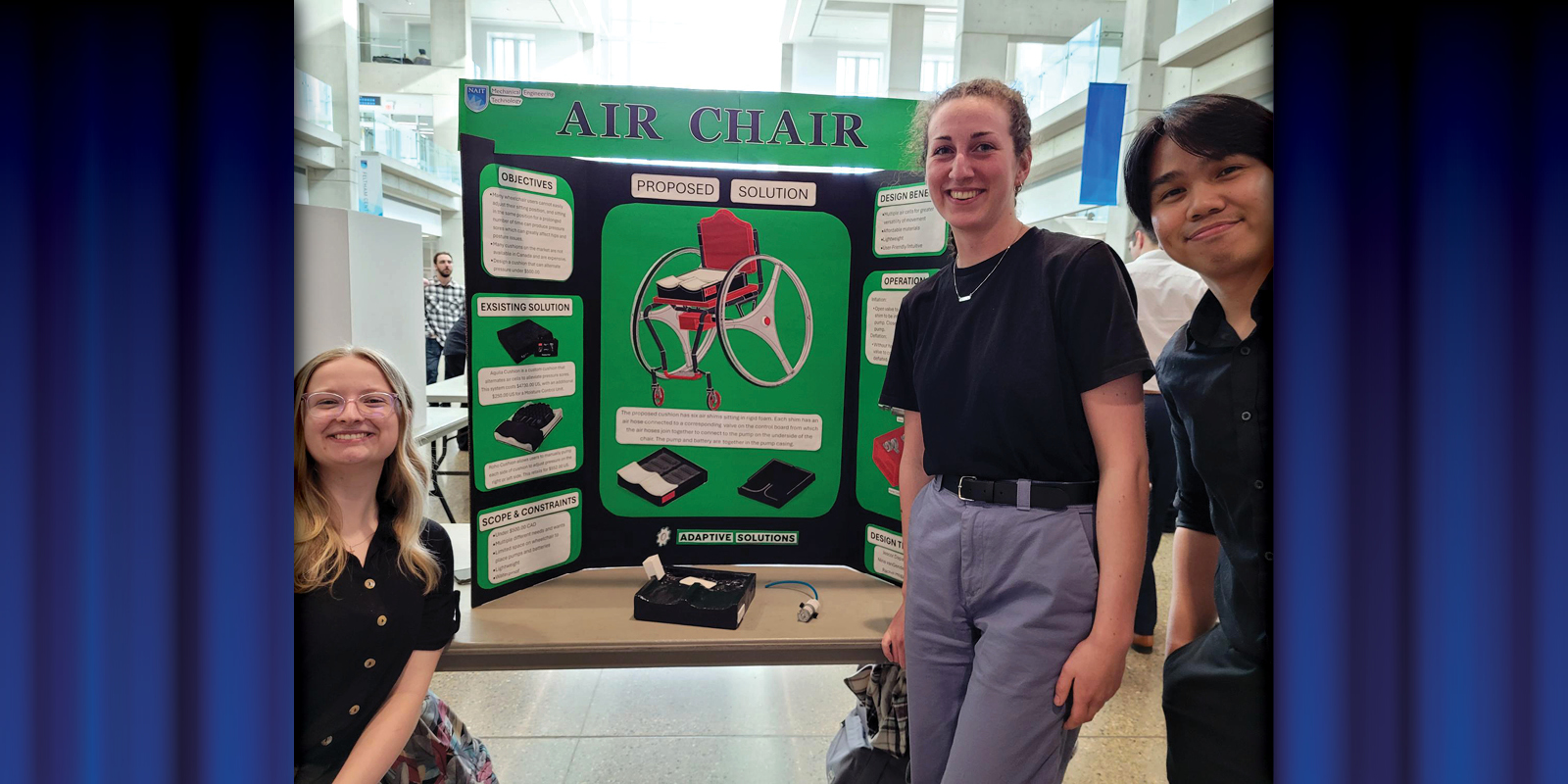

That challenge was the motivation for a capstone project completed by Jescor Dapat, Rachel Mogg and Nina vanGenderen, three soon-to-graduate Mechanical Engineering Technology students.

How do you help someone who spends up to 16 hours a day in a wheelchair enjoy life and opportunities similar to those with greater mobility? First, they adapted their approach to understand those often-overlooked needs.

That done, they started hitting up Amazon for parts for a bespoke, battery-powered, air-filled fully customizable, affordable cushion that has given each of them a deep appreciation of how design can help foster not just wellness but inclusivity.

Simply ingenious

The “Air Chair” came from a group of Edmonton-area wheelchair users with whom program chair Scott Sparling (Mechanical Engineering Technology ’94) has partnered on several student projects. Bean Gill (Medical Radiologic Technology ’03), co-founder of the ReYu Paralysis Recovery Centre and one of the stars of CBC’s Push, served as sponsor.

The challenge appealed to the students as more than a mechanical puzzle. “All three of us just felt like this project could really make a difference,” says vanGenderen, who handled report writing for the group.

What’s more, Mogg could relate. A connective tissue disorder causes her to experience joint instability and occasional dislocation. In severe cases it can require wheelchair use.

“That makes mobility a bit of an issue some days,” says Mogg, who led design work on the Air Chair.

The group sought to make their device easy to use and cheaper than existing models currently too expensive to be widely accessible. “The main purpose of our design is to make things simple for people in wheelchairs to just push a button,” says Dapat, who led the project and liaised with Gill.

“The main purpose of our design is to make things simple for people in wheelchairs.”

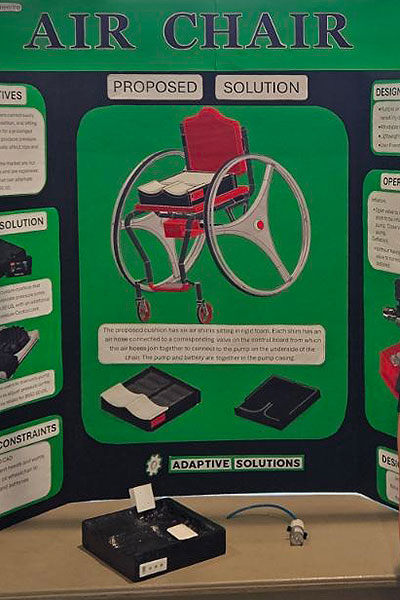

This was accomplished with a cushion consisting of six shims, or small inflatable bladders, connected to an automated pump powered by a battery commonly used for cordless drills. A dial connected to the shims allows users to choose which fill or deflate.

“You open the valve, air fills up and it shifts the person so they’re able to change how they’re positioned,” says Mogg.

“They did a great job of coming up with that balance between trying to invent something and have it come in and at [low] cost,” says Sparling. What’s more, he points out, the shims can easily be exchanged for other sizes, making the concept fit any body – “which I thought was an ingenious idea.”

In the end, Gill was of a similar mind – somewhat to her surprise.

“This might sound bad but, having lived in this world with a disability for almost 12 years, I keep my expectations low.”

She does this to avoid being disappointed by a world that tends to exclude her community by design. “But when I saw their design, I was very impressed by just how simple it is.

What’s more, Gill adds, “It gives you independence because you can do it for yourself.”

Lifelong knowledge

During the four-month project, the three students were able to bring the Air Chair to a state between proof-of-concept and prototype: they know what they need to make it work, how to put it together, and that it will work. But it would take considerably more time to prepare it for market.

During the four-month project, the three students were able to bring the Air Chair to a state between proof-of-concept and prototype: they know what they need to make it work, how to put it together, and that it will work. But it would take considerably more time to prepare it for market.

“We believe that there’s still a lot of improvements that we can make,” says Dapat.

Some wheelchair users from the original group have already expressed interest, encouraging Mogg.

“I really want to continue,” she says, “and even just start with a prototype and see how far we can get making this.”

Gill, too, is encouraged. “I see lots of potential in this,” she says. In addition to cushions for chairs, she sees applications for the technology as thin mats for ICU hospital beds.

In the meantime, there’s other potential within sight. When users of wheelchairs initially spoke to the students, they broadened their perspectives.

“Being able to talk to them and hear about their daily struggles influenced us,” says Mogg. “We want to be able to help.”

For Dapat and vanGenderen, the end result was also more than just a grade.

“It’s not just a project, it’s not just the research,” says Dapat. “It’s something that can help someone make life easier.”

And for the three of them – and for the end users they come to serve throughout their careers, and perhaps the young professionals they go on to mentor – it will likely help them as well. One design doesn’t fit all, they know. What’s easy for one person may not be for another. They don’t take that for granted.

“No matter where they end up,” says Sparling, “I’m pretty sure they’re going to be taking that knowledge with them.”

)