Fashion

A Brief History Of Juneteenth Fashion | Essence

On June 19, African Americans throughout the United States will celebrate Juneteenth, the newest federal holiday. Although celebrated in Texas since 1865, President Joe Biden signed the holiday into law in 2021. However, all of this would not have been possible without the advocacy and efforts of Opal Lee, a Marshall, Texas native with years of experience in education and political organizing, who campaigned for the holiday to be recognized on a federal level. Nonetheless, in the years since its federal recognition, Juneneenth has quickly become commodified.

The unintended consequence of being a federal holiday is the erasure and loss of its deep, rich, and vast cultural traditions and heritage. Juneteenth is not a Black holiday or a Southern holiday, but specifically a Black Texan holiday. And June 19 deserves to be celebrated as such.

For instance, Juneteenth is not the actual name of the holiday. It was first celebrated as “Emancipation Day” or “Jubilee Day” by Afro-Texans in Galveston and freedom colonies, free Black settlements, throughout the state. In 1872, Reverend Jack Yates and a collective of religious and business leaders in Houston raised funds to purchase 10 acres of land to create Emancipation Park for the city’s official Juneteenth celebration. Around the 1890s, Afro-Texans began to use “Juneteenth.” A decade later, Juneteenth spread to Texas’ neighboring states of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma. Despite the spread of the Afro-Texan holiday to surrounding areas, large-scale celebrations were minimized.

“Many whites and even some Blacks saw Juneteenth as un-American because it focused attention on a dark period in U.S. History,” wrote Professor Shennette Garrett-Schott in her 2013 journal article “When Peace Come”: Teaching the Significance of Juneteenth.” “Ironically Juneteenth was considered unpatriotic or disloyal to the United States, and there was a wave of deadly lynching and racial violence that occurred between 1919 and 1921.”

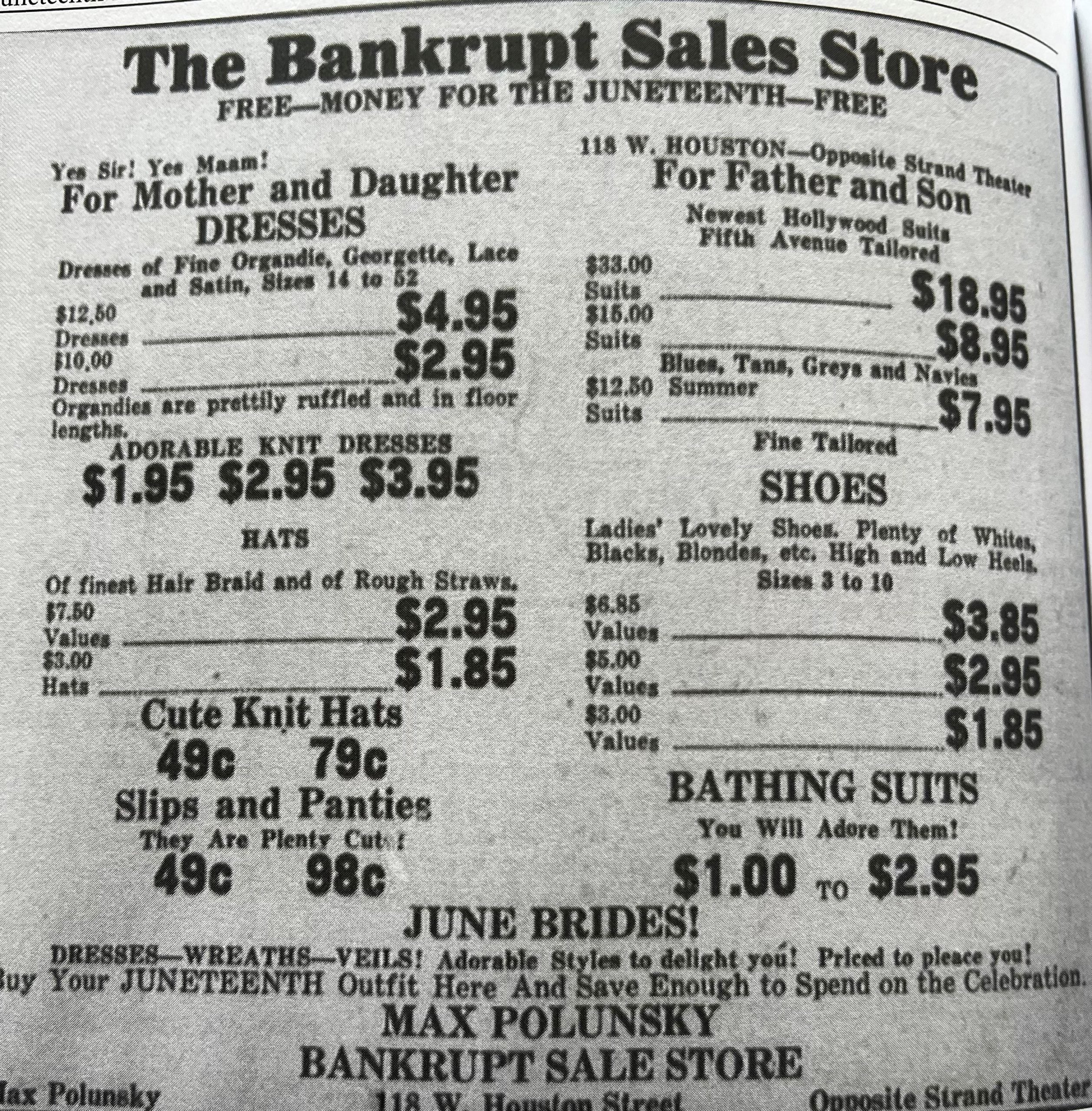

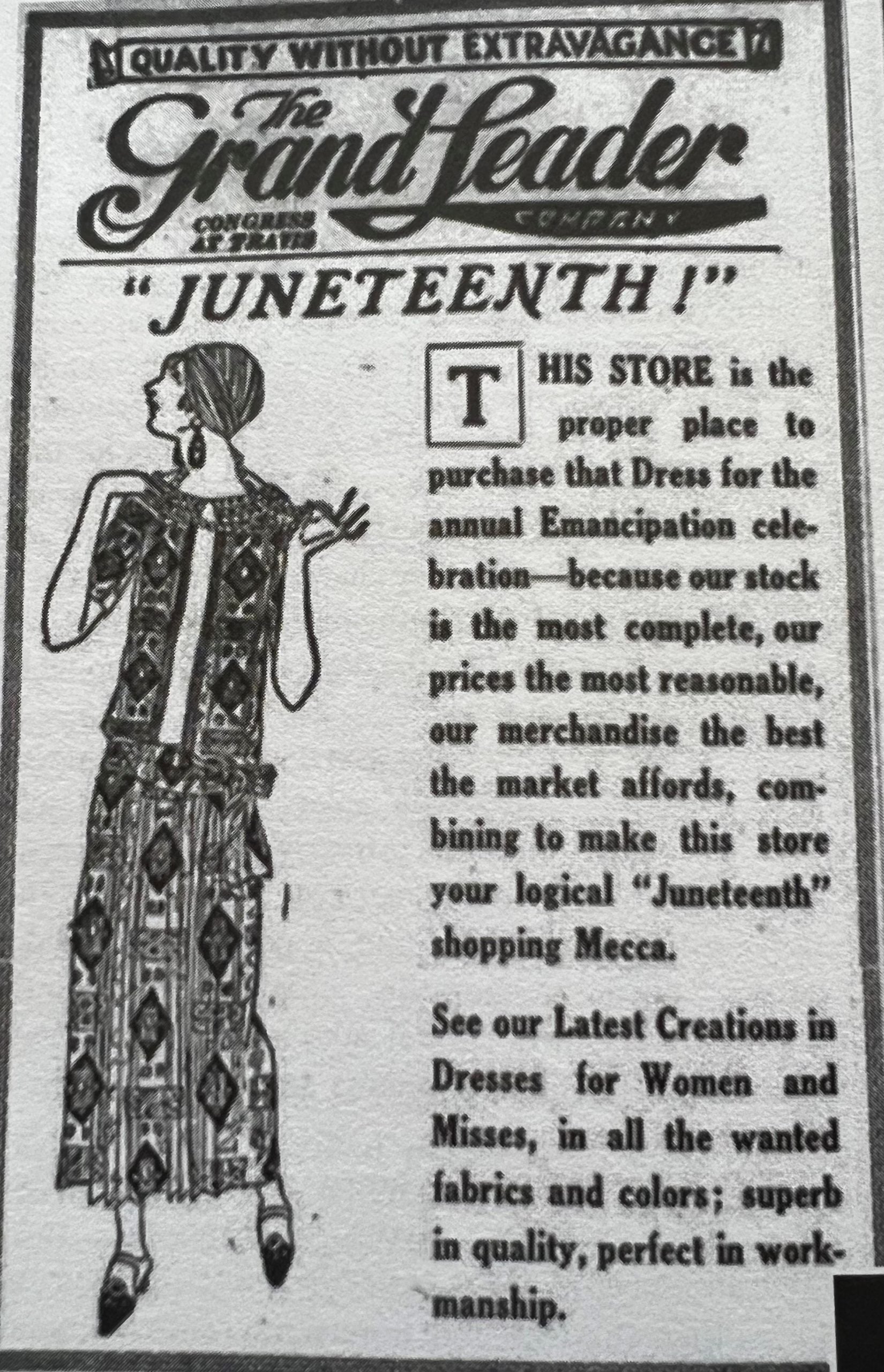

In the midst of this fear, the Juneteenth celebrations continued. At a 1922 Juneteenth ball in Waxahachie, Texas, “Uncle Mose”, a well known character in the town, donned “a display of varicolored neckties that were so brilliant as to hurt one’s eyes,” according to The Fort Worth Morning Register. At a 1934 celebration of Juneteenth in Dallas, a dress code was implemented. “All the color will be confined to the crimsons, yellows, and casket purples of the women’s dresses and the rainbow hues of neckties,” as reported by The Dallas Morning News.

Community wide celebrations of Juneteenth in Texas would not return until 1936. Antonio Maceo Smith, a pivotal leader in the Dallas Negro Chamber of Commerce, spearheaded this revival by acquiring federal funding to create the Hall of Negro Life, “the first official recognition of African American achievements by a world’s fair in the United States,” which was launched at the Texas Centennial Exposition in 1936.

A constant among all Juneteenth celebrations, whether big or small, urban or rural, was the attire. Afro-Texans and their descendants not only celebrated with song, dance, food, but also through fashion. Prior to Juneteenth, clothing was dictated by the slave codes and social norms of the time. Yet, even in that period of enslavement, they would adorn the clothes of their owners and throw parties in their absence. Post enslavement, dress was a way to recontextualize and reconstruct their image and their identity. No longer were they the enslaved, but an Afro-Texan, an African-American.

“You’d ought to seed ’em pullin’ off them croaker-sack clothes when master says we’s free,” said Rube Witt in an interview with Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project.

Pictures of the earliest Juneteenth celebrations depict African Americans in their Sunday best. Women in monochromatic white dresses embellished with lace, flowers, and a hat to block out the sun or capture God’s eye. Men in three piece-suits with canes, giving off the aura of an established gentleman. Sarah Tate elected to use her first funds as a free woman to purchase white cotton fabric, which she turned into a dress.

Seamstresses like Tate were among the first to create a distinct identity for African-Americans through fashion. Patches of homemade cloth, woven together with flannel. Assorted colors of whites, reds, blues, yellows, and browns. The dying of the fabric in the West African way of using plants and natural materials to achieve a particular hue. The medley of American and African practices to create a new set of apparel to adorn oneself as a new person, a free person.

It would be decades later until Ben Haith would create the first flag to commemorate Juneteenth in 1997. Prior to its creation, some African Americans would use the Pan-African flag. Its colors of red, black, and green are symbolic of the Pan-African movement.

Compared to the Juneteenth Flag, created by Haith and illustrated by Lisa Jeanne Graf; there are distinct differences. First, the colors of red, white, and blue represent that “American Slaves, and their descendants were all Americans.” Second, the flag’s symbols tell a story. The star is an ode to Texas, but also all African-Americans living in the 50 states. The burst signifies a new beginning, similar to a nova. The arc embodies “the opportunities and promise that lay ahead for Black Americans.” Although Haith and Graf make no mention of the Texas state flag, which shares the same colors and meanings as the American flag, one could argue that there is a connection between the two.

One thing everyone can agree on is that “It’s the Freedom for Me” is not indicative of Juneteenth. Nor is red, black, and green themed paraphernalia or red velvet flavored ice creams. There is no need to purchase Juneteenth goods and services for major corporations and brands. But there is a need for continued education about this holiday. If one is in need of ways to commemorate it, read about the ways in which it was celebrated in the past and what its originators and pioneers did. The songs, the dance, the food, the clothes, the advocacy. There are a few ways in which to celebrate Juneteenth, but never forget that it is a Texas holiday. And Black Texans are still suffering under intense state repression. There is still so much work to be done in order for our ancestors’ dreams to come true.

)