Jobs

AI’s hidden workers are stuck in dead-end jobs – Taipei Times

The challenge for data workers is that their jobs are harder to visualize in the same,

concrete way you can imagine a young boy sewing tennis shoes in a dimly lit warehouse

-

By Parmy Olson

/ Bloomberg Opinion

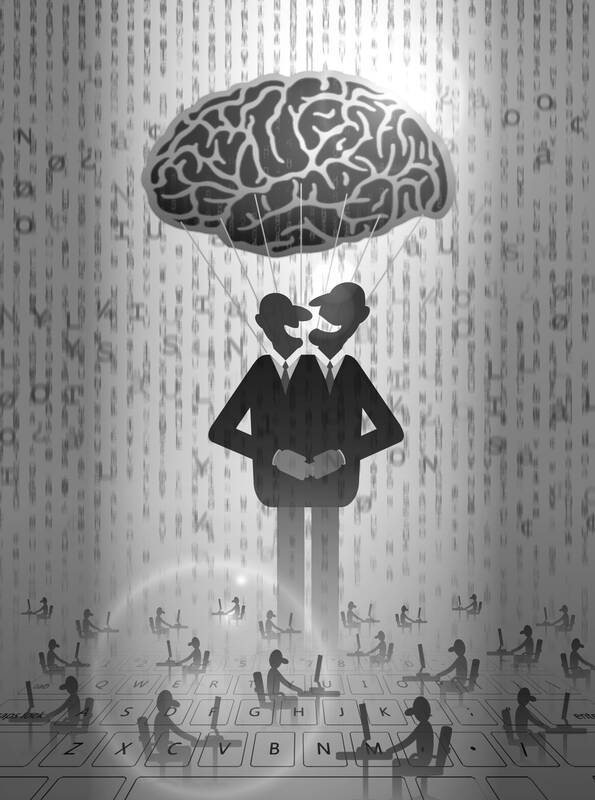

You might have heard that revolutionary artificial intelligence (AI) sits on old-world foundations. The supply chain churning out generative AI tools like ChatGPT has highly paid executives and researchers at the top, and at the bottom, working stiffs who toil at screens training algorithms. About 150 million to 430 million people do such work, World Bank estimated. These people annotate images, text and audio, create bounding boxes around objects in images and, more recently, write haiku, essays and fictional stories to train the sophisticated tools that could eventually replace people like me.

They also exist in a kind of economic stasis. “I’ve never met a worker who would tell me ‘This job gave me the chance to buy my house or send my kids to university,’” said Milagros Miceli, a researcher at the Distributed AI Research Institute and Weizenbaum Institute, who has worked with scores of data workers across the world.

Miceli recalls speaking to about a dozen data-labeling workers earning about US$1.70 an hour in an Argentina slum in 2019. When she returned in 2021, none had moved on and their wages had barely increased. They were still living below the poverty line.

Illustration: Yusha

Workers often have to take second jobs or night shifts, said Madhumita Murgia, the AI editor of the Financial Times whose recent book, Code Dependent, features their stories from across the developing world.

One woman who worked for Samasource Impact Sourcing in Nairobi, for instance, could not support herself and her daughter on her salary, and had to move in with her parents, Murgia said.

The job itself is precarious. Another worker in Bulgaria could not make rent because she was suspended from accepting paid tasks after complaining about night shifts.

“You’re one step away from everything unraveling,” Murgia said.

End customers are the likes of Microsoft Corp and OpenAI, some of the most valuable firms in the world.

“It’s like the factory worker in the Philippines who doesn’t realize the dress they’re stitching is going to be a US$3,000 gown,” Murgia added.

There is also precious little of that time-honored aspiration for the developing world: upward mobility. Murgia found that data workers were not transitioning to higher-paying digital jobs. “They’re still confined to low-value work,” she said.

Leaders of data-labeling firms often start with noble intentions to help pull people out of poverty, but they have struggled to get corporate customers to pay higher rates as competition in their field has increased. As such, most data work platforms do not have policies in place to ensure their workers earn at least the local minimum wage, a 2021 survey from the Oxford Internet Institute showed.

Take this job ad seeking “professional translators” in Nigeria that offers up to US$17 an hour to help train generative AI models. That is well below the average rate for Nigerian translators, who tend to start at US$25 an hour, according to Good Firms, a client-reviews Web site.

The ad comes from Remotasks, the main platform of San Francisco-based AI start-up Scale AI Inc, which just raised US$1 billion from investors including Amazon.com Inc in one of the year’s largest financing rounds. Scale AI did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The company and rivals like San Francisco-based Samasource Impact Sourcing Inc, Argentina’s Arbusta S.R.L. and Bulgaria’s Humans in the Loop play a critical role in the AI supply chain, but for years now have typically paid just enough for workers to maintain a living, Murgia and Miceli said.

That might continue even as data work becomes more complex. Platforms like Scale AI have been looking for more skilled workers, including artists and people with creative-writing degrees to write short stories for training AI systems, according to instruction documents seen by Miceli.

While those offer higher wages, they are still below what people with degrees should be earning.

Researchers said the appetite for such work is growing, but with few incentives to provide an equitable wage, it is hard to see workers’ economic status improving.

Training AI is already horrifically expensive due to the cost of chips and cloud computing. Venture capital firm Sequoia Capital recently calculated that the AI industry spent US$50 billion on Nvidia Corp chips to train AI last year, but only made about US$3 billion in revenue.

That spells fewer opportunities for the people underpinning the AI revolution and shows yet again that the technology’s true transformative effects have been in entrenching economic power.

Perhaps we can learn something from Nike Inc. Back in the 1990s, the company faced an enormous backlash for the long hours and meager wages its workers in developing nations earned. Over time, consumer boycotts and pressure from the media led Nike to put in stricter labor policies. It has spent millions of dollars on improving conditions and pay.

The challenge for data workers is that their jobs are harder to visualize in the same, concrete way you can imagine a young boy sewing tennis shoes in a dimly lit warehouse, and that can make it harder for their advocates to rally support. However, tech companies should remember that poor working conditions at the bottom of their supply chain can also lead to substandard AI. That is problematic at a time when the public is more wary than ever of buzzy models that hallucinate. The answer to that is not rocket science: Pay the data workers more and treat them better, too.

Parmy Olson is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. A former reporter for the Wall Street Journal and Forbes, she is author of We Are Anonymous. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Comments will be moderated. Keep comments relevant to the article. Remarks containing abusive and obscene language, personal attacks of any kind or promotion will be removed and the user banned. Final decision will be at the discretion of the Taipei Times.

)