It’s been a strange year for representations of British royalty. In March, major photo agencies issued a rare “kill notice” on a photo of Catherine, Princess of Wales after evidence emerged that it had been tampered with. In May, Jonathan Yeo’s official portrait of King Charles sparked online discussion with its arresting red background. And now a portrait of Catherine commissioned by Tatler from Zambian-British artist Hannah Uzor is provoking yet more debate with its questionable degree of likeness.

In fact, British monarchs have grappled with issues of representation, accuracy and flattery in portraits since the Middle Ages, as the stories of these five monarchs show.

1. Henry VII (reigned 1485-1509)

Lambetz Falera/Wiki, CC BY-SA

From the reign of Edward I until 1504, England’s silver currency carried a generic, full-face representation of a nonspecific king.

The image was intended to convey universal royal power, rather than individual likeness. Henry VII had a relatively weak claim to the throne when he defeated Richard III in 1485, but he recognised the value of the visual arts in promoting his reign. In 1504, his government ordered a reform of the coinage, issuing silver coins with a new likeness of Henry VII in profile. The coins showed the king with shoulder-length curly hair – and a rather prominent nose.

Clearly Henry felt that the older, generic likeness was no longer adequate for the needs of modern monarchy. By tying the currency’s regal authority to his own image, he reinforced his legitimacy, but also looked back to ancient imperial precedents, triggering a new trend for royal portraits that truly resembled their sitters.

2. Mary Queen of Scots (reigned 1542-1567)

On February 10 1567, Lord Darnley, husband of Mary, Queen of Scots, died in an explosion in Edinburgh. On subsequent nights, mysterious voices were heard in the streets, accusing Mary’s rumoured paramour, the Earl of Bothwell James Hepburn, of murder.

Placards appeared depicting the queen as a bare-breasted mermaid, holding a falconry lure to symbolise her siren-like seduction of Bothwell. As a symbol of prostitution, the mermaid undermined Mary’s virtue, presenting her as a scheming, lustful woman.

National Archives

A horrified Mary summoned her ministers in an attempt to discover the name of the artist, but a sketch of the placard had already made its way to England, where it survives to this day in the English State Papers.

Although sent with a note condemning the “undutiful” behaviour of Mary’s subjects, it was filed away by Elizabeth I’s chief advisor William Cecil as an example of negative intelligence about Mary, whose execution he later orchestrated.

3. Elizabeth I (reigned 1558-1603)

Recognising the damage that bad representations could do to a monarch’s reputation, Elizabeth I’s regime made several attempts to control her image. As early as 1563, a proclamation was drafted prohibiting portraits containing “errors and deformyties”. This was never enacted, but a similar warrant issued at the end of her reign, in 1596, ordered the destruction of unflattering portraits of the queen.

Wiki Commons

In the 1590s, when Elizabeth was in her 50s, artists often employed the “mask of youth” in her portraits: a fictive, never-ageing face pattern, intended to allay fears about Elizabeth’s advancing age and lack of heirs.

But one artist who did not follow this trend was Isaac Oliver, whose miniature (created circa 1590) presents an unusually accurate likeness of the ageing queen. The portrait was apparently never finished, and historians have sometimes assumed that Elizabeth rejected it.

In fact, the portrait had a successful afterlife, even serving as the face pattern for the Ditchley Portrait (1592), which apparently delighted Elizabeth with its vision of the queen as a quasi-divine giantess.

4. George III (reigned 1760-1820)

When the French Revolution began in 1789, many in Britain feared the revolutionary spirit would spread. In 1792, the Royal Proclamation Against Seditious Writings and Publications was issued – primarily as a response to the popularity of Thomas Paine’s book Rights of Man (1791), which argued in favour of popular revolution against despotic monarchs and hereditary aristocracy.

The royal proclamation outlawed “all such Attempts which aim of the Subversion of all regular Government within this Kingdom”, and looked set to impinge on the rights of caricaturists such as James Gillray, who regularly parodied members of the government and royal family.

National Portrait Gallery, CC BY-SA

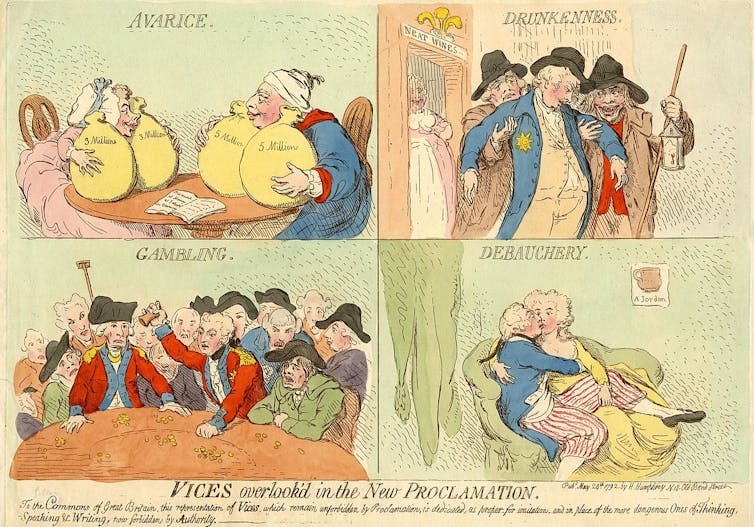

Gillray’s retort, Vices overlook’d in the New Proclamation (1792), took aim at the king’s hypocrisy, representing George III and Queen Charlotte as “avarice” clutching moneybags, and the Prince of Wales, future George IV, as “drunkenness”.

A year later, the French king was beheaded and France declared war on Britain, leading many caricaturists to tone down their representations of the royal family for a time. But fear of sedition remained.

In 1795, two acts known collectively as the Gagging Acts made it a treasonable offence to incite people to hatred or contempt of the king or government “by publishing any printing or writing” – a clause that encompassed caricatures like Gillray’s.

5. Victoria (reigned 1837-1901)

Royal Collection Trust

Not all unpopular royal portraits were suppressed for being offensive – they could also be deemed too sexy. Queen Victoria commissioned a portrait from the German painter Franz Xaver Winterhalter in 1843, as a surprise gift for her husband Prince Albert’s 24th birthday.

She referred to it in her diary as “the secret picture”. Kept in Albert’s private writing room at Windsor, it depicts Victoria in a low-cut, translucent dress, leaning against a red cushion, her lips slightly parted.

After her death in 1901, the portrait was apparently thought “too overtly sexual” to be shown to the public, and was only finally put on display in 1977.

)